“The rivers flow not past, but through us, thrilling, tingling, vibrating every fiber and cell of the substance of our bodies, making them glide and sing.” John Muir

I shove myself against the big, yellow raft and hop aboard as it slowly drifts from the beach into the middle of the Colorado River. Lees Ferry, Arizona is the launch-point for all Grand Canyon rafting trips, and I find myself on the very first trip of the season. I dreamt of this moment over the four years I have worked in the office for an adventure travel company. Sitting at my desk, I stared at photos of red and brown streaked canyons, green fern-lined grottos, and waterfalls roaring out of the middle of a wall powered by hidden springs. As my expectations go, in 17 days we will emerge at Lake Mead a little more weathered and little less fried by the daily connection to digital screens.

As the youngest kid in my family, the title “wild child” was a badge of honor. Like most kids growing up in the 90s, my cousins and I were lovingly-but-lightly supervised and endlessly curious about anything that resulted in scraped knees and adrenaline. As an adult, the term “wild child” still reminds me of those barefoot adventures, tirelessly running around outside and wearing various layers of dirt—memories that are seeming farther away these days as the glow of my work computer shines brighter. So I’m headed to the Grand Canyon, one of the wildest places in the country, and am hoping to shake awake that fearless, adventurous inner-kid that has been napping on and off through college and a career. Scraped knees and dirty feet included.

We pull into the current, and I stare up at the colorfully layered walls of Marble Canyon as Stef, the captain of the 18-foot baggage boat I am lounging on, (wo)mans the oars. My bubbling excitement to be here is now translating into the incessant need to talk, and Stef patiently answers all of my questions about the walls and the water around us. Stef is a veteran boatwoman, and begins her summers guiding on the Yampa—the last free-flowing tributary of the very river we are floating on. Once the natural flows ebb and the water gets too low, she moves to the Green River—also a tributary of the Colorado—and spends her nights camping riverside. Her stories paint images of a Neverland-esque place where adults relax and kids run free. Just the kind of place I am hoping will help me shake off the rust that sets in after years of 7-day-a-week connectivity.

We pull into camp, set up the kitchen, chat with guests and (maybe just me) feel like headless chickens establishing the order-of-operations for the coming nights. Exhausted, I finally lay out my sleeping bag on the sand and look up. The stars are perfectly framed by high canyon walls, and without much of a moon to steal the brightness of the celestial spread, the lights look like a river flowing and reflecting the very one we are using as a highway. There is more light than blackness in that sky- the clear, glowing specks take up more space than the night’s darkness can overwhelm.

A few days into the trip we slowly approach Red Wall Cavern—an amphitheater carved at the base of the canyon wall that was estimated by John Wesley Powell to be large enough to hold 50,000 people (modern estimates are a bit more conservative). I jump off the boat and climb up the sand into the cavern, letting the size of the place wash over me as I spin on my toes to take it in. Our trip leader tells how this and all the river we’ve been exploring would be underwater if it wasn’t for the tooth-and-nail battle conservationist fought against a dam project. It dawns on me that someone actually dreamt of putting a dam just downstream, which would have flooded the upper reaches of the Grand Canyon, the same way I dreamt of floating through this place for years. The vulnerability of a place so gargantuan seems impossible, but the holes drilled in the canyon walls for the dam construction make it’s possible demise impossible to ignore. Perhaps the people interested in building a dam here never got to visit this cavern.

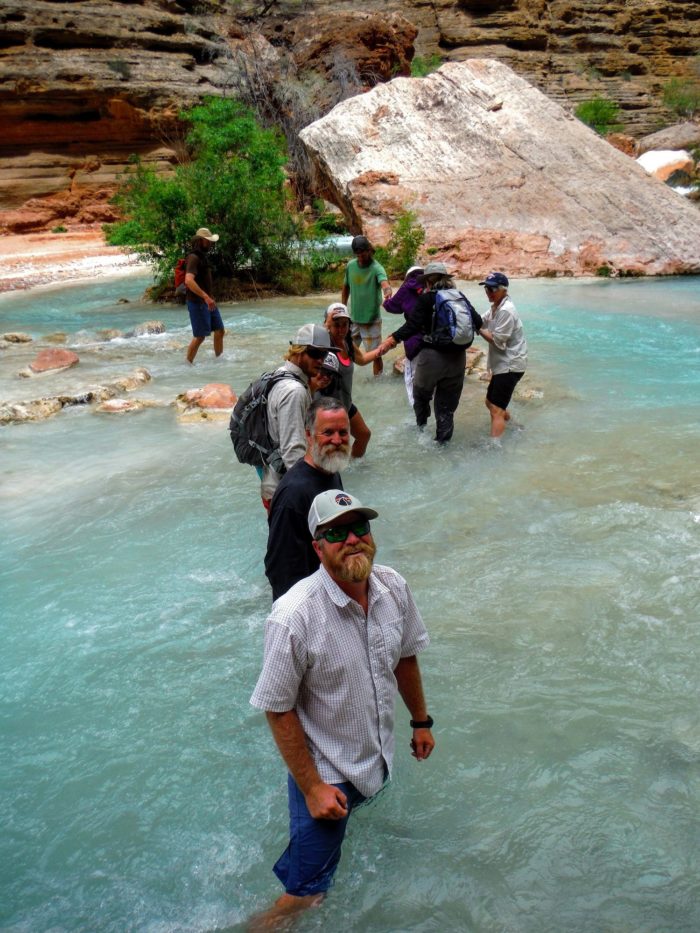

Each day we continue downstream, and each night we camp riverside under the stars. It’s effortless to be lulled into an easy sense of existence- deep in a canyon only 1% of its five million visitors get to see. Out of reach of cell phones and Wi-Fi, with the only responsibility being the safety, care and enjoyment of the rest of our companions, one can simply “be”—exist in the wildest of places, float on the most ancient of rivers, and connect with something deeper and more lasting than Instagram or Snapchat can offer. Here it’s about survival, exploration and companionship. We hike together from our camp up to the Nankoweap Ruins, a native granary far above the river that has lasted intact for thousands of years. We climb through the side canyon high above Deer Creek, each of us silently wondering about the ancient handprints across the seemingly impassable gap. We swim in the cold, white-blue waters of the little Colorado and listen as a guide explains the Piute’s belief that this is where their people came from. And we help each other cross Havasu Creek hand-in-hand, using the same trails and putting our feet in the same sand as people were doing thousands of years ago. We take pains to tread lightly through a natural legacy that has taken millions of years to build.

The last day of the trip I find myself back on Stef’s boat, easy laughter flitting between us like old friends. Over the past 16 days, our conversations slowly made me feel like she was giving me admittance into a top-secret club where adventures are a given and 100 days annually spent outside are typical. After spending many more than a 100 days in front of a computer screen and feeling progressive with my stand-up desk, I begin to think maybe I have missed something big somewhere between childhood and this thing called adulthood.

As we take off our PFDs for the last time, it dawns on me that very soon my cell phone will have service and my hair will meet its old friend “shampoo”. I can’t decide which part of me I like and which part of me I mourn- the one that can’t wait to slip into clean sheets and send out text messages to the people I love, or the one that, childlike, trusted the river to take me into this wilderness and share some of its long-learned lessons along the way.

While I left the canyon behind the day of our take-out and returned to the city I call home, the Grand Canyon’s vastness and antiquity have filled me with a sense of order and peace in what can feel like a chaotic world. For a little while, personal connection replaced screen connectivity, the faithful movement of the water replaced the unpredictable highways of home, and the peace that comes with starlight replaced the buzzing unease that comes with streetlights. With those joys, images of dammed water filling Red Wall Cavern, flooding the bank below Nankoweap, or reaching Havasu creek have also flitted across my imagination as I settle back into daily life. The Canyon taught me that ancient, natural places are just as vulnerable to destruction as the city green spaces paved over for parking lots, and that our survival as people is one that’s intertwined with the natural places we escape to searching for re-calibration in a world demanding constant engagement. When those places are gone, it’s hard to imagine us as humans also sticking around. Like constricted water trying to move past a dam, people disconnected with nature and it’s wild places will begin to push back at what is an unyielding wall of concrete and buildings, looking for space to expand and move where space will no longer exists. In the words of John Muir, “Thousands of tired, nerve-shaken, over-civilized people are beginning to find out that going to the mountains is going home; that wildness is a necessity.” The Grand Canyon became a place for my inner wild-child to expand, and with it, the awareness that without our wild places to explore, we would be lost to a world of digitization.